Based on the positive test results from the 1:12 scale model, the design of Quidnon nouveau-retro Chinese Junk sails is almost fully baked. But there are a couple more bothersome problems to solve. Junk sails are attached to the mast using parrels, which are short lines or straps running along the battens and around the mast. This generally works rather well, but produces a couple of unintended effects:

1. The sail tends to rotate forward on the mast because the part of it that is aft of the mast is larger and therefore heavier. To counteract this tendency, Junk sails employ an additional control line called a “luff hauling parrel” which is laced through the front of the battens and then around the mast. It is yet another line to adjust, and it would be nice to get rid of it. Depending on the design of the sail, other minor control lines may be necessary as well, further complicating the handling.

2. On one of the tacks (depending on which side of the sail the mast is) the sail drapes over the mast, distorting its shape and making it a less efficient airfoil. Without this distortion, each panel of Quidnon’s sails forms a very efficient airfoil, similar to a Lateen sail. This is an important effect when sailing hard on the wind, making one tack significantly more efficient than the other.

To get rid of these unintended effects, I would like to introduce a new piece of rigging: the batten standoff. These are basically sticks that fasten onto the battens at one end and onto the parrels near the mast on the other. The batten standoffs do two things: they keep the sail from sliding fore-and-aft on the mast, and they push the sail away from the mast. Under most circumstances they are self-tending and don’t require adjustment.

At their ends near the mast, the standoffs are daisy-chained on lines—batten standoff lanyards—that hang down from the end of the halyard. These lines make sure that the standoffs hang almost but not quite horizontally: they have to slope slightly toward the mast, so that they don’t ride up the mast when under compression. If the mast is to starboard of the sail, it may be necessary to walk forward and pull down the batten standoff lanyards after reefing while sailing on a port tack, when the standoffs are under compression. When they are under tension, they will be pulled into position by the battens and settle a bit further by themselves due to gravity. Thus, when reefing while on a port tack, it is best to release the sheet first, allowing the sail to luff, then release the halyard partway, then haul in and tighten the reefing line, and finally haul in the sheet to power the sail back up.

The batten standoffs have to be cheap, light, reliable and easy to jury-rig or to replace when they fail. To achieve this, I intend to make them out of aluminum pipe. The pipe is cut to length, the ends are tapped, and stainless steel threaded rod is screwed into the ends. The mast end consists of a triple clamp, with two horizontal slots for the parrels and one vertical slot for the lanyard, all tightened together using a single Nylock nut. The batten end, which goes through a hole in the batten, has a couple of washers and a Nylock. There will have to be 24 batten standoffs (6 battens × 2 sides × 2 sails) and they will cost a bit of money to fabricate (out of aluminum pipe and bar and stainless steel threaded rod, two rubber washers and two Nylocks). But I think that the improved performance and the elimination of extra control lines will make it worth it.

There is also an element of perfectionism to it. There is some amount of extra joy to be had in looking up and seeing a perfect, maximally simple, undistorted form of the sail lit up by the sun against the sky.

The purpose of this project is to design and mass-produce kits for a floating tiny house that can sail. It combines high-tech modeling and fabrication and low-tech assembly that can be carried out DIY-style on a riverbank or a beach. This boat is a four-bedroom with a kitchen, a bathroom/sauna, a dining room and a living room. The deck is big enough to throw dance parties. It can be used as a river boat, a canal boat or even a beach house. It's rugged and stable enough to take out on the ocean.

Saturday, December 16, 2017

Friday, December 15, 2017

Hull Shape Revisited

|

| Click to enlarge |

After many design iterations, the additional ballast was confined to a steel scrap-filled cement block bolted in place under the chain locker, which is, in turn, located under the cockpit. An entire sequence of steps was drawn up for dropping it out, with the boat in the water, before sweating the boat ashore using the anchor winch (to serve as a temporary beach house) and for winching and bolting it back into place with the boat once again in the water. But it was, essentially, a complication. And now, after four years of thinking through all of the various details, happily, it turns out to be unnecessary.

One of the worst mistakes one can make is to build based on an imperfect plan: build in haste, as it were, repent at leisure. Four years may seem like a long time to design just one boat. Most boat designers worry about time to market, remaining competitive, keeping the money coming in and other such issues. I am not worried in the least about any of that. I just want to design a very good boat that I am going to like, and that plenty of others will too. I am quite a few years yet away from retirement, my son is a few years yet from being able to serve as master of a ship, and so I am not going to rush. When designing something and faced with a problem, bad ideas are the first to arrive, while the good ones can take a very long time.

That said, the project is moving along. Thanks to the crowdfunding exercise of last summer, we are now running on licensed/donated CAD software (instead of lots of evaluation versions) and have a new, powerful, dedicated server box for doing renderings and running simulations. There is a list of a dozen or so to-do items, none of them huge, that have to be worked out before we can have the plans analyzed and signed off on by a marine architect, and we have the money to pay him. The questions to be answered are along the lines of “How thick should we make the fiberglass”, “What gauge steel do we use” and so on. Once past that point we will accept equity investment and start building hulls in several places around the world where people are waiting for us.

That is actually a good position to be in, making it a very good time to try very hard to resolve the few remaining unsatisfactory issues with the design. The solid ballast box is one issue. The fact that the sails are much more efficient on one tack than the other when sailing close-hauled is another. We’ll deal with that one later; today we kill the solid ballast box.

When I drew up Quidnon’s initial lines, I tried to follow Phil Bolger’s advice about square boats—that complicating their hull shapes adds more to their complexity and expense than it adds to their performance. But here is a counterexample: I believe that this change will subtract from the expense (no more solid ballast box or the mounting brackets it requires; simpler hull shape aft because the recess for the box is no longer needed) while boosting performance.

Previously, the bottom of the hull forward of amidships consisted of the bottom and two sides joined at two chines. The angle between them was 100º aft of amidships while forward from amidships it decreased until they met at a point at top and center of the bow, where the angle between them went to 0. The modification is that forward of amidships there are now four surfaces rather than three that come together to a flat spot at top and center of the bow. The bottom is now formed from two surfaces, and the centerline, called the stem, is buried a bit deeper than the two chines. This modification adds the exact amount of buoyancy forward that’s needed to make the boat sit on its lines without the fixed ballast mounted aft.

But then there are the other benefits. First, there is the improved motoring performance. When sailing on almost any point of sail Quidnon heels over a bit and presents a lopsided “V” to the water, which cuts very well through the waves. But when motoring the hull sits level and the flat surface presented to the waves at the bow slows it down. Just a small amount of deadrise at the bow (that’s the term for the “V” shape of the bottom) is enough to deflect the flow of water to the sides rather than making the boat bounce up and down while pushing an energy-wasting roll of froth with the bow (a boat with “a bone in its teeth” is Bolger’s term for that effect).

Simulations using Orca3D software showed that prior to this change to the hull shape Quidnon would actually take less power to push forward at hull speed when loaded with 10 tons of cargo then when motoring empty. This was because when empty the stern would be quicker to bog down. Getting rid of the cargo box will lighten the stern, and the added buoyancy at the bow will extend the effective waterline length, both of these changes counteracting this tendency. Moreover, when motoring along rivers and canals with the masts dropped there is no reason not to drain the water ballast, to lighten the load. Under these circumstances, having solid ballast mounted aft would be most unhelpful. When motoring without the ballast, Quidnon may be able to push its hull speed somewhat. We’ll run simulations to confirm this.

One more benefit: the slight “V” shape at the bow will not only deflect the flow of water but also of floating debris and ice chunks. Without this feature, the debris would wash directly past the prop, possibly fouling it. And as for ice, Quidnon is by no means meant to serve as an icebreaker, but it should be able to sail through many forms of ice. Sailing through ice is a big topic, and I will take it up separately later, but Quidnon’s bow turns out to be almost perfect for powering through pancake ice, slush, thin crust and other varieties of frozen water that occur in the fall and the spring. Having an “icebreaker” bow surfaced with roofing copper may allow Quidnon to extend the season a month or so in each direction.

Lastly, this change to the bow shape adds a welcome visual feature to what was previously a rather blank and featureless bow. Now, Quidnon’s hull shape is not designed to titillate—it will do enough other things that other boats can’t do to make up for its somewhat unexciting hull shape—but having a bow that looks more like a bow than like half a transom is a nod in the general direction of boating fashion that some people would I am sure welcome.

Tuesday, October 10, 2017

World's Largest Playground

|

| Lake Baikal |

The boats used depend on the application: the seaworthier sailboats—keelboats and catamarans—for the ocean, while motor boats are restricted to the coasts, the canals and the rivers. There are exceptions: plenty of keelboats try to get through the Intracoastal and often end up running aground, and every autumn a steady stream of sailboats and catamarans arrives from Canada via the Erie Canal and Hudson River with their masts down (to make it under the bridges) and their decks a mad tangle of rigging.

There is a lot to like about cruising: the relaxed, unhurried lifestyle (you move at your own pace with no schedules to hurry you along); there is the chance to explore new places that are not easily accessible except by water and therefore not likely to be overrun with tourists; the intimate contact with nature and the chance to observe it daily at close range.

One of the biggest problems with cruising is that it’s boring: virtually all of the cruising grounds have been mapped out, with detailed cruising guides telling you where to go and what to look at. Essentially, when you go cruising, you are signing up to do something that’s already been done.

Another problem with cruising is rich people. Now, there is nothing wrong with being rich, and a good quote to remember is Deng Xiaoping’s 致富光荣 (zhìfù guāngróng): “To get rich is glorious!” The problem is with people who try to act rich around you while you are trying to ignore all of that competitive nonsense and just have a good time. To quote me: “To act rich is in bad taste.”

An associated problem is that cruising tends to be expensive: the industrial sector that supplies the boats is competitive, and it competes on the basis of ostentation—in sportiness and luxury—while catering primarily to those who want to act rich. And what sits at the intersection of sportiness and luxury is a financial black hole: the boats that result from this process are maintenance nightmares, and the most common topic of discussion among cruisers is getting their broken stuff fixed, wherever they happen to end up.

And the offshoot of all this is that most cruisers happen to be over the hill. The vast majority of those I’ve seen are baby boomers squandering their children’s inheritance on expensive toys, marina transient fees (which cost as much as hotel room stays) and lots of trips to local restaurants. Most of them are reasonably friendly and personable, but what they mostly talk about is insipid: the quality of the food and the service, the weather and, of course, what broke and how they fixed it or are planning to. If this doesn’t sound too adventurous or exciting to you, then perhaps you are right.

And then it occurred to me that there is a cruising destination that hasn’t been explored at all: Russia. Russia has the largest network of navigable waterways in the world: over 100,000 km long. The European part of it is 6,500 km long, all of it dredged to 4 m (13 feet). A system of canals connect it into a single network of waterways that reaches from the Baltic to the Ural mountains and from the Arctic Ocean to the Black Sea. The following map shows all of the navigable waterways in light blue.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Of particular interest is the area just inland from St. Petersburg, which is on the Baltic Sea. River Neva, which is short and wide, connects it to Ladoga Lake, which is the largest lake in Europe. It has islands, fjords and plenty of good sailing. From there is the somewhat smaller Onega Lake, and rivers and canals then run on to Moscow and a ring of cities around it, which are some of the most spectacular travel destinations in Russia, featuring medieval fortresses and monasteries, most of them accessible from the water. South from there, the mighty Volga River takes you through most of the rest of Russia’s historical heartland. Then, via the Volga-Don Canal, you can cross over to River Don, which takes you to the Black Sea.

There are a few logistical problems with going on such a cruising adventure. One is that no foreign-flagged vessels are allowed on Russia’s inland waterways. Another is that a local skipper, who speaks fluent Russian and knows the local regulations, is an absolute requirement. Also, any small craft that goes on this adventure has to be maximally self-sufficient: there are few to no marinas offering yacht repair services to be found. Lastly, the cruising season runs from May through October. It can be stretched by a few weeks each way further south, but nobody in their right mind would brave River Neva before the end of April, when Onega Lake has dumped its load of winter ice into the Baltic. But none of these problems is insoluble.

Specifically, it has occurred to me that Quidnon, by its design, makes it a splendid choice as a platform for such an adventure. It is simple, rugged, quickly and cheaply constructed from commonly available materials and parts, is safe in both deep and shallow water, and can be set up for comfortable living in a harsh climate. I will explain the details of this in the next post. Meanwhile, please enjoy the scenery!

|

| Caspian Sea |

|

| Volga Delta |

|

| Yenisei River |

|

| Ladoga Lake |

Saturday, August 5, 2017

The Self-Sufficient Haulout

A self-sufficient sailor needs to be able to get his boat in and out of the water either with minimal assistance or entirely unassisted.

This need arises in a variety of situations, both common and less so:

1. To deal with maintenance and emergencies.

1.A. To redo the bottom paint and to make emergency repairs that cannot be done with the boat in the water. With Quidnon, the list of such emergencies is much smaller than with most boats. There is no engine shaft, cutlass bearing or propeller; these are integral to the outboard engine, which is easy to pull out for servicing. There are no through-hulls below the water line; raw water intakes for the ballast tanks are via siphons. The bottom is surfaced with roofing copper that lasts longer the useful lifetime of the boat. The sides below the waterline need to be scrubbed and painted periodically, but this can be done with the boat drying out at low tide. Marine growth on the bottom, which cannot be reached while the boat is drying out, simply gets crushed and ground off against the sand or gravel and falls off. Still, there are situations when a haulout is needed for maintenance.

2.B. To get out of the water if a hurricane or a typhoon is bearing down on you. The easiest thing to do is to run Quidnon into the shallows in a sheltered spot and to run long lines out to surrounding rocks and trees. But an even better option is to haul it clear of the water first. While other yachts are busy hunting around for a hurricane hole (a sheltered spot with enough water to get in and out without running aground) or wait in line at a boatyard or a marina for an (expensive) emergency haulout, the captain of a Quidnon has plenty of options.

2. To turn Quidnon into a waterside home.

2.A. Suppose you arrive at a tropical island and decide that you want to spend a few months there, subsisting on fresh-caught fish and crabs, coconuts, sea bird eggs, growing a patch of taro or yucca and generally lazing around. There is nobody around to assist you. You enter the lagoon, find a nice sheltered spot with an easy grade up a white sand beach, let Quidnon nose up to it, jump overboard, wade ashore, walk the anchor ashore, dragging the chain, and bury it in the sand. Then you drain the ballast tanks and unbolt and drop the solid ballast box that fits snugly in a recess under the cockpit. Finally, you spend an hour or so working the anchor winch while placing coconut palm logs under the hull for it to roll over. Voilà! Quidnon is now a beach house: it doesn’t rock, the bottom doesn’t accumulate seafood, and getting ashore is as easy as climbing down a ladder.

2.B. You spend your summers cruising inland lakes, rivers and canals, catching and drying fish, hunting wild game and harvesting wild-growing fruits and vegetables along the shoreline. Autumn arrives, it starts snowing and the waterways start icing over. Before they become icebound and dangerous you pick a spot where you want to overwinter: somewhere sheltered, with plenty of firewood available locally. If you are lucky, you find a spot that has something like a beach, with no more than a 10º grade. Failing that, you grab a shovel and an axe (to chop through tree roots) and dig down a slope. Then you follow the same procedure as above. If you are quite far north where temperatures stay below freezing for months on end, it would make sense to insulate the hull on the outside by piling snow against it (snow is an excellent insulator, and is free).

There are lots of other, less extreme scenarios. For example:

3.A. You either own or lease a patch of land next to a waterway and build a boat ramp. Then, equipped with nothing more than a boat trailer and a pickup truck or an SUV you can either live on a Quidnon ashore or put it in the water and go cruising. This would be ideal in colder climates, where you would prefer to stay put during the winter. In going through the Intracoastal Waterway, I saw plenty of places where such a lifestyle would make sense. People there tend to have a full-size house and a half-size boat, but why not have a full-size boat and a small, utilitarian structure on land used as a workshop and for storage?

3.B. For those who have a shoreside dwelling, it is perfectly reasonable to own a Quidnon but only use it during the warmer months. But storing a boat, whether in the water or on shore, is often an expensive proposition. But there are plenty of creative ways to store boats in close proximity to boat ramps. For example, people who own vacation properties are often quite happy to have you pay a little bit of rent—much less than a marina or a boatyard would charge—to store your boat on their land during the off-season. Again, all you need is a trailer, a good-sized pickup truck or SUV and a boat ramp that’s nearby. (If it’s farther away, you will need highway permits and signal cars, because Quidnon qualifies as a “wide load.”)

The mechanics of a self-sufficient Quidnon haulout are as follows.

1. Get rid of all ballast. Fully ballasted, Quidnon weighs in at 12 tons, 8 of which is ballast. Of that, 5 tons is water ballast, which can be made to disappear by draining the tanks. The remaining 3 tons is solid ballast consisting of steel scrap encapsulated in a concrete block bolted into a recess in the bottom directly under the cockpit and held in place by several large bolts and a purchase. To remove the solid ballast, with the boat in the water, it is necessary to rig and tighten the purchase, undo the nuts on the bolts (which are along the sides of the chain locker below the cockpit, so the cockpit sole needs to be removed to access them), then ease the ballast down to the bottom using the purchase. Finally you would probably want to attach a line and a buoy to the ballast block before letting go of it, so that you can find and retrieve it later.

2. If your haulout spot has overhead obstructions (tree branches, power lines) remove the sails and drop the masts. This can be done by one person using a comealong. Once down, the sails and the masts are lashed down on top of the deck arches, to keep them safe and out of the way. On the other hand, if your haulout spot is exposed, you may want to leave the masts up and mount wind generators on top of them, to avail yourself of the free, though somewhat unreliable electricity.

3. Let Quidnon nose up to a grade no more than 10º. The maximum slope for boat ramps is 15% grade, which is 8.5º; most beaches are less than that. If you are hauling over ground solid enough for logs to roll, all you need are the rollers; if not, you will need to lay down some logs to serve as rails. Walk the anchor ashore and bury it, as described above. Work a log under the skids, then work the anchor winch to move the boat forward. The first log will try to squirm out and will require some gentle persuasion using a sledgehammer. Repeat. Catch the logs that slip out the back and move them to the front.

4. The amount of time required to move Quidnon 100 feet up a 10º grade using a crab winch (where a single person rocks a winch handle back and forth) is around an hour of steady effort (assuming a person can generate 100W of power) not including the time needed to move and pound in logs, drink water, curse, swat insects and whatever else. Reasonably, it adds up to a few hours’ work for one reasonably fit person. Of course, if you have a 1kW generator, an electric winch and a couple of helpers you can get this accomplished in around 20 minutes.

Quidnon will come equipped with rails, integral to the keelboard trunks and surfaced with bronze angle to distribute the load and to resist abrasion. The round logs are not included and would need to be procured locally. Driftwood is often a good, free source, and can be collected beforehand in preparation and stored on deck. It can be used as firewood afterward.

Once Quidnon is far enough from the water, it is important to level it, by digging down or by pounding in wedges. It is rather important that it doesn’t try to roll back into the water one stormy night while you are asleep. On the other hand, if your haulout spot is in an area that is considered dicy from a security standpoint, you may want to crank the boat around, so that it faces the water, and rig up a system so that a few blows with a sledgehammer and a few minutes on the anchor winch will cause it to roll back into the water (or onto the ice) and, one would hope, away from danger.

Incidentally, although this is hardly their main function, the rails over which Quidnon is rolled ashore can also be used to turn Quidnon into a sled, over ice. Ice provides a nearly frictionless surface, and it should be possible for a few people to haul Quidnon to a new location a few miles over ice. This trick may come in handy if halfway through the winter the game or the firewood at a haulout site on one side of a river becomes depleted. A particularly adventurous Quidnon skipper might even consider putting up a bit of sail and taking advantage of a winter windstorm to try a bit of ice sailing. (It would make sense to put up a bit of each sail, and to use the sheets for steering, because the rudders won’t be of much use when gliding over ice… unless the adventurous skipper takes the time to fit them with skates.

If these scenarios seem outlandish to you, then consider the more prosaic ones: while all the other skippers are waiting around with their wallets wide open—for the diesel mechanic to fix their engine, for a scuba diver to cut away the dock line that got wrapped around their prop, for the travelift to haul them out of the water and put them up on jacks so that they can paint their bottom or fix a leaky through-hull, or for a crane to remove their mast so that it can be worked on it—you would be off on your next adventure, self-sufficient and free.

This need arises in a variety of situations, both common and less so:

1. To deal with maintenance and emergencies.

1.A. To redo the bottom paint and to make emergency repairs that cannot be done with the boat in the water. With Quidnon, the list of such emergencies is much smaller than with most boats. There is no engine shaft, cutlass bearing or propeller; these are integral to the outboard engine, which is easy to pull out for servicing. There are no through-hulls below the water line; raw water intakes for the ballast tanks are via siphons. The bottom is surfaced with roofing copper that lasts longer the useful lifetime of the boat. The sides below the waterline need to be scrubbed and painted periodically, but this can be done with the boat drying out at low tide. Marine growth on the bottom, which cannot be reached while the boat is drying out, simply gets crushed and ground off against the sand or gravel and falls off. Still, there are situations when a haulout is needed for maintenance.

2.B. To get out of the water if a hurricane or a typhoon is bearing down on you. The easiest thing to do is to run Quidnon into the shallows in a sheltered spot and to run long lines out to surrounding rocks and trees. But an even better option is to haul it clear of the water first. While other yachts are busy hunting around for a hurricane hole (a sheltered spot with enough water to get in and out without running aground) or wait in line at a boatyard or a marina for an (expensive) emergency haulout, the captain of a Quidnon has plenty of options.

2. To turn Quidnon into a waterside home.

2.A. Suppose you arrive at a tropical island and decide that you want to spend a few months there, subsisting on fresh-caught fish and crabs, coconuts, sea bird eggs, growing a patch of taro or yucca and generally lazing around. There is nobody around to assist you. You enter the lagoon, find a nice sheltered spot with an easy grade up a white sand beach, let Quidnon nose up to it, jump overboard, wade ashore, walk the anchor ashore, dragging the chain, and bury it in the sand. Then you drain the ballast tanks and unbolt and drop the solid ballast box that fits snugly in a recess under the cockpit. Finally, you spend an hour or so working the anchor winch while placing coconut palm logs under the hull for it to roll over. Voilà! Quidnon is now a beach house: it doesn’t rock, the bottom doesn’t accumulate seafood, and getting ashore is as easy as climbing down a ladder.

2.B. You spend your summers cruising inland lakes, rivers and canals, catching and drying fish, hunting wild game and harvesting wild-growing fruits and vegetables along the shoreline. Autumn arrives, it starts snowing and the waterways start icing over. Before they become icebound and dangerous you pick a spot where you want to overwinter: somewhere sheltered, with plenty of firewood available locally. If you are lucky, you find a spot that has something like a beach, with no more than a 10º grade. Failing that, you grab a shovel and an axe (to chop through tree roots) and dig down a slope. Then you follow the same procedure as above. If you are quite far north where temperatures stay below freezing for months on end, it would make sense to insulate the hull on the outside by piling snow against it (snow is an excellent insulator, and is free).

There are lots of other, less extreme scenarios. For example:

3.A. You either own or lease a patch of land next to a waterway and build a boat ramp. Then, equipped with nothing more than a boat trailer and a pickup truck or an SUV you can either live on a Quidnon ashore or put it in the water and go cruising. This would be ideal in colder climates, where you would prefer to stay put during the winter. In going through the Intracoastal Waterway, I saw plenty of places where such a lifestyle would make sense. People there tend to have a full-size house and a half-size boat, but why not have a full-size boat and a small, utilitarian structure on land used as a workshop and for storage?

3.B. For those who have a shoreside dwelling, it is perfectly reasonable to own a Quidnon but only use it during the warmer months. But storing a boat, whether in the water or on shore, is often an expensive proposition. But there are plenty of creative ways to store boats in close proximity to boat ramps. For example, people who own vacation properties are often quite happy to have you pay a little bit of rent—much less than a marina or a boatyard would charge—to store your boat on their land during the off-season. Again, all you need is a trailer, a good-sized pickup truck or SUV and a boat ramp that’s nearby. (If it’s farther away, you will need highway permits and signal cars, because Quidnon qualifies as a “wide load.”)

The mechanics of a self-sufficient Quidnon haulout are as follows.

1. Get rid of all ballast. Fully ballasted, Quidnon weighs in at 12 tons, 8 of which is ballast. Of that, 5 tons is water ballast, which can be made to disappear by draining the tanks. The remaining 3 tons is solid ballast consisting of steel scrap encapsulated in a concrete block bolted into a recess in the bottom directly under the cockpit and held in place by several large bolts and a purchase. To remove the solid ballast, with the boat in the water, it is necessary to rig and tighten the purchase, undo the nuts on the bolts (which are along the sides of the chain locker below the cockpit, so the cockpit sole needs to be removed to access them), then ease the ballast down to the bottom using the purchase. Finally you would probably want to attach a line and a buoy to the ballast block before letting go of it, so that you can find and retrieve it later.

2. If your haulout spot has overhead obstructions (tree branches, power lines) remove the sails and drop the masts. This can be done by one person using a comealong. Once down, the sails and the masts are lashed down on top of the deck arches, to keep them safe and out of the way. On the other hand, if your haulout spot is exposed, you may want to leave the masts up and mount wind generators on top of them, to avail yourself of the free, though somewhat unreliable electricity.

3. Let Quidnon nose up to a grade no more than 10º. The maximum slope for boat ramps is 15% grade, which is 8.5º; most beaches are less than that. If you are hauling over ground solid enough for logs to roll, all you need are the rollers; if not, you will need to lay down some logs to serve as rails. Walk the anchor ashore and bury it, as described above. Work a log under the skids, then work the anchor winch to move the boat forward. The first log will try to squirm out and will require some gentle persuasion using a sledgehammer. Repeat. Catch the logs that slip out the back and move them to the front.

4. The amount of time required to move Quidnon 100 feet up a 10º grade using a crab winch (where a single person rocks a winch handle back and forth) is around an hour of steady effort (assuming a person can generate 100W of power) not including the time needed to move and pound in logs, drink water, curse, swat insects and whatever else. Reasonably, it adds up to a few hours’ work for one reasonably fit person. Of course, if you have a 1kW generator, an electric winch and a couple of helpers you can get this accomplished in around 20 minutes.

Quidnon will come equipped with rails, integral to the keelboard trunks and surfaced with bronze angle to distribute the load and to resist abrasion. The round logs are not included and would need to be procured locally. Driftwood is often a good, free source, and can be collected beforehand in preparation and stored on deck. It can be used as firewood afterward.

Once Quidnon is far enough from the water, it is important to level it, by digging down or by pounding in wedges. It is rather important that it doesn’t try to roll back into the water one stormy night while you are asleep. On the other hand, if your haulout spot is in an area that is considered dicy from a security standpoint, you may want to crank the boat around, so that it faces the water, and rig up a system so that a few blows with a sledgehammer and a few minutes on the anchor winch will cause it to roll back into the water (or onto the ice) and, one would hope, away from danger.

Incidentally, although this is hardly their main function, the rails over which Quidnon is rolled ashore can also be used to turn Quidnon into a sled, over ice. Ice provides a nearly frictionless surface, and it should be possible for a few people to haul Quidnon to a new location a few miles over ice. This trick may come in handy if halfway through the winter the game or the firewood at a haulout site on one side of a river becomes depleted. A particularly adventurous Quidnon skipper might even consider putting up a bit of sail and taking advantage of a winter windstorm to try a bit of ice sailing. (It would make sense to put up a bit of each sail, and to use the sheets for steering, because the rudders won’t be of much use when gliding over ice… unless the adventurous skipper takes the time to fit them with skates.

If these scenarios seem outlandish to you, then consider the more prosaic ones: while all the other skippers are waiting around with their wallets wide open—for the diesel mechanic to fix their engine, for a scuba diver to cut away the dock line that got wrapped around their prop, for the travelift to haul them out of the water and put them up on jacks so that they can paint their bottom or fix a leaky through-hull, or for a crane to remove their mast so that it can be worked on it—you would be off on your next adventure, self-sufficient and free.

Thursday, June 1, 2017

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Thursday, May 18, 2017

A Boat for the Reluctant Sailor

A couple of days ago I conducted an interesting social experiment. I joined the largest Facebook group dedicated to sailing a cruising, and started a discussion thread about QUIDNON:

“Looking for some advice from group members. For the past two years I have been working on a boat design with two other engineers. It is a 36-foot houseboat, with private accommodations for 3 couples and 2 single people. It is also a surprisingly seaworthy and competent sailboat. We've tested a radio-controlled scale model and it sails really well. Now we are looking forward to building the first full-size hull. It's going to be a kit boat, featuring high-tech manufacturing and rapid DIY assembly. Don't hold back, what do you think?”

The results were roughly as follows:

• It doesn’t have the proper lines of a sailing yacht, and is therefore ugly.

There is a certain image that sailboats are supposed to have, and anything that doesn’t fit with the image is by definition ugly. It is like approaching people who like Ferraris and Lambourghinis and trying to sell them a VW Bus.

• It doesn’t have the right elements to be a top-notch performer under sail, and wouldn’t win any races.

Saying “But it’s a houseboat!” doesn’t seem to have any effect. How well does a houseboat have to sail in order to be “A Houseboat that Sails”? Apparently, it has to be able to win ocean races. Just being able to move house whenever you like without burning fossil fuels… What was that? Hey, look, a squirrel!

• It doesn’t look expensive enough.

This last point was not made explicitly, but I sensed great discomfort when I mentioned how cheap it is, or the fact that moderately skilled people can assemble the boat from a kit on any riverbank or beach, roll it into the water and sail off, or that it uses an outboard engine in an inboard well to avoid the expense and the stink of a diesel, or that it never needs to be hauled out and have its bottom repainted because the bottom is clad in roofing copper… You see, an important function of owning a sailboat is to tell the world how rich you are. And what this boat tells the world is that you are happily living well below your means. Oh, the cognitive dissonance!

• It looks better without the masts and the sails.

Again, sailboats aren’t supposed to look like what it looks like. But without the masts, it looks like some kind of strange barge-like thing, doesn’t intrude on the sailboat space and is therefore inoffensive. Plus, if it no longer sails, then there is nothing further to discuss: problem solved! (But that is, in fact an option: if you don’t want to sail, you don’t need to install the mast tabernacles or the masts. Just place plugs in the 6-inch holes where the mast tabernacles penetrate the deck.)

The creature comforts, unprecedented in a 36-foot sailboat, such as three bedrooms with queen-size beds and full privacy, or the sauna, or a deck large enough to throw dance parties, left them entirely unimpressed. I guess sailboats are meant to be cramped, claustrophobic and uncomfortable. And houseboats aren’t supposed to be able to sail, at all.

I even came in for some insults, slander and abuse. One opinionated character with the last name Aass (can’t make this up!) made quite an… Aass of himself by claiming that I am clueless and running a scam. But that comes with the territory; after all, it’s Facebook, the natural habitat of the lonely half-crazed idiot.

In short, QUIDNON does not appeal to cruising sailors or racing sailors (and that’s pretty much who responded). To be sure, some people found the project fascinating and, based on the blog stats, went and read all about it. And some of them wished me and the project the very best luck. But the most vocal people were also the most negative. In all, it appears that most of the people who responded did so because QUIDNON rubbed them the wrong way in any one of several ways: it doesn’t fit the glamorous image of yachting, it is useless for either sport or ostentation, and it shows people the way to live and enjoy themselves on the water for very little money. Anathema!

And so who does QUIDNON appeal to? After all, 10,000 people visit this blog every month, close to 100 have already supported the crowdfunding campaign, and a dozen or so are seriously interested in building one, or having one built for them, once the design gets shaken out at full size.

There is one particular demographic that QUIDNON is explicitly designed to appeal to: wives of men who want to live aboard and like to sail. The vast majority of women have absolutely no interest in living aboard any of the typical commercially produced sailboats. Why is it so cramped? Where do you put the shoes? Where is the closet space I need? Why is there no bathtub? Why does it lean so much all the time? Why is the deck weirdly shaped and has strange hardware all over it? Why can’t it be like a proper deck/patio with room for a couple of chaise-lounges and a beach umbrella? Why do I keep bumping my head against things? Where do I hang the potted plants? Why is the refrigerator so tiny? A man may convince a woman to live aboard for a while even without coming up with good answers to any of these questions, but then longer-term the project is doomed.

And so the options are:

1. Abandon the dream of living aboard a sailboat and pay lots of money to live on land.

2. Get a houseboat and abandon the dream of sailing.

3. Get a houseboat to live on and a sailboat to sail around on, and go broke paying for both.

4. Get a divorce and live on a sailboat. (This happens surprisingly often; the call of the sea is sometimes stronger than the funny stuff Cupid coats his arrow tips with.)

5. Get a QUIDNON. It is every bit a houseboat and answers all of the above questions. In designing it, I thought extremely hard about putting in all the things that would convince my wife that living aboard is still reasonable and, on the other hand, about getting rid of all the things that she has hated about living aboard.

How well should a houseboat sail? Sailing performance comes at a cost in comfort, safety and skill level. Sailing a 36-foot high-performance racer is something of an art. Sail handling is quite demanding, and if you make a mistake you can capsize, hurt yourself or rip a very expensive sail. While sailing, you have to handle lines that are under a lot of tension—enough to rip your hands off if you aren’t careful. And none of that is necessary.

People who live on a houseboat and sometimes move house under sail have no specific reason to want to master that art and achieve that level of performance. They just want to get from Point A to Point B with a minimum of effort and drama. Other than moving house, the main reason to go sailing is to pass time, with company on board. This is best done on medium-breezy, sunny summer days. Motor away from the dock, put the sails up, leave the engine idling away just in case, and noodle about the harbor. Time is not of the essence; safety and comfort are. And, of course, cost.

QUIDNON’s sails are controlled using just four ropes (called “lines”) and all of them are led right to the cockpit, go through clutch blocks, and then disappear under the cockpit floor, where they spool themselves up on take-up reels. Yes, you do need to learn what they are called and what they do, but that’s about it.

• Halyard: used to hoist the sail up the mast. The clutches for the other three lines have to be released before you do that.

• Reefing line: opposite of the halyard; used to reduce the area of sail that is up and keep it taut. The more wind there is, the less sail you have to raise to push QUIDNON along at its maximum warp 7.5 knots (8.5 MPH, 13.9 km/h). QUIDNON’s sails can be reefed down to just the upper two panels.

• Two sheets, one on each side: these pull the sail toward the centerline while keeping it from twisting. The closer to the wind you sail, the more you haul in the sheet.

Of these lines, only the halyard requires the use of the winch. To get a sail up (which is quite heavy), you release the clutches, loop the halyard around the anchor winch and crank.

There is more to sailing than that, but this information, plus what you can learn from any introductory book on sailing, will be enough for you to sail a QUIDNON.

QUIDNON should be able to make ocean passages in good weather. The preferred direction is definitely with the wind rather than against it. Going with the wind stretches out the waves; going against the wind causes them to bunch together. It is like the difference between driving through a hilly countryside and driving down a rutted, potholed road. Because of its blunt bow and high topsides QUIDNON may not be able to make good progress to windward in all conditions. But it should do well downwind in almost all conditions.

Keep in mind, almost the entire planet was explored and colonized using sailing ships that could barely go to windward at all. For every mile they made good to windward, they made two moving sideways. And so they mostly moved with prevailing winds or waited for favorable winds. They made laps around the North Atlantic going clockwise, to take advantage of the Coriolis effect: the rotation of the Earth causes both water and air to move clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the southern. And QUIDNON can probably do the same, safely and comfortably.

“Looking for some advice from group members. For the past two years I have been working on a boat design with two other engineers. It is a 36-foot houseboat, with private accommodations for 3 couples and 2 single people. It is also a surprisingly seaworthy and competent sailboat. We've tested a radio-controlled scale model and it sails really well. Now we are looking forward to building the first full-size hull. It's going to be a kit boat, featuring high-tech manufacturing and rapid DIY assembly. Don't hold back, what do you think?”

The results were roughly as follows:

• It doesn’t have the proper lines of a sailing yacht, and is therefore ugly.

There is a certain image that sailboats are supposed to have, and anything that doesn’t fit with the image is by definition ugly. It is like approaching people who like Ferraris and Lambourghinis and trying to sell them a VW Bus.

• It doesn’t have the right elements to be a top-notch performer under sail, and wouldn’t win any races.

Saying “But it’s a houseboat!” doesn’t seem to have any effect. How well does a houseboat have to sail in order to be “A Houseboat that Sails”? Apparently, it has to be able to win ocean races. Just being able to move house whenever you like without burning fossil fuels… What was that? Hey, look, a squirrel!

• It doesn’t look expensive enough.

This last point was not made explicitly, but I sensed great discomfort when I mentioned how cheap it is, or the fact that moderately skilled people can assemble the boat from a kit on any riverbank or beach, roll it into the water and sail off, or that it uses an outboard engine in an inboard well to avoid the expense and the stink of a diesel, or that it never needs to be hauled out and have its bottom repainted because the bottom is clad in roofing copper… You see, an important function of owning a sailboat is to tell the world how rich you are. And what this boat tells the world is that you are happily living well below your means. Oh, the cognitive dissonance!

• It looks better without the masts and the sails.

Again, sailboats aren’t supposed to look like what it looks like. But without the masts, it looks like some kind of strange barge-like thing, doesn’t intrude on the sailboat space and is therefore inoffensive. Plus, if it no longer sails, then there is nothing further to discuss: problem solved! (But that is, in fact an option: if you don’t want to sail, you don’t need to install the mast tabernacles or the masts. Just place plugs in the 6-inch holes where the mast tabernacles penetrate the deck.)

The creature comforts, unprecedented in a 36-foot sailboat, such as three bedrooms with queen-size beds and full privacy, or the sauna, or a deck large enough to throw dance parties, left them entirely unimpressed. I guess sailboats are meant to be cramped, claustrophobic and uncomfortable. And houseboats aren’t supposed to be able to sail, at all.

I even came in for some insults, slander and abuse. One opinionated character with the last name Aass (can’t make this up!) made quite an… Aass of himself by claiming that I am clueless and running a scam. But that comes with the territory; after all, it’s Facebook, the natural habitat of the lonely half-crazed idiot.

In short, QUIDNON does not appeal to cruising sailors or racing sailors (and that’s pretty much who responded). To be sure, some people found the project fascinating and, based on the blog stats, went and read all about it. And some of them wished me and the project the very best luck. But the most vocal people were also the most negative. In all, it appears that most of the people who responded did so because QUIDNON rubbed them the wrong way in any one of several ways: it doesn’t fit the glamorous image of yachting, it is useless for either sport or ostentation, and it shows people the way to live and enjoy themselves on the water for very little money. Anathema!

And so who does QUIDNON appeal to? After all, 10,000 people visit this blog every month, close to 100 have already supported the crowdfunding campaign, and a dozen or so are seriously interested in building one, or having one built for them, once the design gets shaken out at full size.

There is one particular demographic that QUIDNON is explicitly designed to appeal to: wives of men who want to live aboard and like to sail. The vast majority of women have absolutely no interest in living aboard any of the typical commercially produced sailboats. Why is it so cramped? Where do you put the shoes? Where is the closet space I need? Why is there no bathtub? Why does it lean so much all the time? Why is the deck weirdly shaped and has strange hardware all over it? Why can’t it be like a proper deck/patio with room for a couple of chaise-lounges and a beach umbrella? Why do I keep bumping my head against things? Where do I hang the potted plants? Why is the refrigerator so tiny? A man may convince a woman to live aboard for a while even without coming up with good answers to any of these questions, but then longer-term the project is doomed.

And so the options are:

1. Abandon the dream of living aboard a sailboat and pay lots of money to live on land.

2. Get a houseboat and abandon the dream of sailing.

3. Get a houseboat to live on and a sailboat to sail around on, and go broke paying for both.

4. Get a divorce and live on a sailboat. (This happens surprisingly often; the call of the sea is sometimes stronger than the funny stuff Cupid coats his arrow tips with.)

5. Get a QUIDNON. It is every bit a houseboat and answers all of the above questions. In designing it, I thought extremely hard about putting in all the things that would convince my wife that living aboard is still reasonable and, on the other hand, about getting rid of all the things that she has hated about living aboard.

How well should a houseboat sail? Sailing performance comes at a cost in comfort, safety and skill level. Sailing a 36-foot high-performance racer is something of an art. Sail handling is quite demanding, and if you make a mistake you can capsize, hurt yourself or rip a very expensive sail. While sailing, you have to handle lines that are under a lot of tension—enough to rip your hands off if you aren’t careful. And none of that is necessary.

People who live on a houseboat and sometimes move house under sail have no specific reason to want to master that art and achieve that level of performance. They just want to get from Point A to Point B with a minimum of effort and drama. Other than moving house, the main reason to go sailing is to pass time, with company on board. This is best done on medium-breezy, sunny summer days. Motor away from the dock, put the sails up, leave the engine idling away just in case, and noodle about the harbor. Time is not of the essence; safety and comfort are. And, of course, cost.

QUIDNON’s sails are controlled using just four ropes (called “lines”) and all of them are led right to the cockpit, go through clutch blocks, and then disappear under the cockpit floor, where they spool themselves up on take-up reels. Yes, you do need to learn what they are called and what they do, but that’s about it.

• Halyard: used to hoist the sail up the mast. The clutches for the other three lines have to be released before you do that.

• Reefing line: opposite of the halyard; used to reduce the area of sail that is up and keep it taut. The more wind there is, the less sail you have to raise to push QUIDNON along at its maximum warp 7.5 knots (8.5 MPH, 13.9 km/h). QUIDNON’s sails can be reefed down to just the upper two panels.

• Two sheets, one on each side: these pull the sail toward the centerline while keeping it from twisting. The closer to the wind you sail, the more you haul in the sheet.

Of these lines, only the halyard requires the use of the winch. To get a sail up (which is quite heavy), you release the clutches, loop the halyard around the anchor winch and crank.

There is more to sailing than that, but this information, plus what you can learn from any introductory book on sailing, will be enough for you to sail a QUIDNON.

QUIDNON should be able to make ocean passages in good weather. The preferred direction is definitely with the wind rather than against it. Going with the wind stretches out the waves; going against the wind causes them to bunch together. It is like the difference between driving through a hilly countryside and driving down a rutted, potholed road. Because of its blunt bow and high topsides QUIDNON may not be able to make good progress to windward in all conditions. But it should do well downwind in almost all conditions.

Keep in mind, almost the entire planet was explored and colonized using sailing ships that could barely go to windward at all. For every mile they made good to windward, they made two moving sideways. And so they mostly moved with prevailing winds or waited for favorable winds. They made laps around the North Atlantic going clockwise, to take advantage of the Coriolis effect: the rotation of the Earth causes both water and air to move clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the southern. And QUIDNON can probably do the same, safely and comfortably.

Thursday, April 27, 2017

Talk in Boston

I'll give a talk and Q&A on QUIDNON at the Artisan's Asylum in Somerville, MA at 8pm on Thursday, May 4th. Hope to see you there.

Sunday, April 23, 2017

Ridiculously versatile

The world is full of boats that do just one thing quite well. QUIDNON is not one of them: it does a great number of things adequately and just one thing ridiculously well.

Ocean yachts are designed for ocean cruising and racing. They make poor houseboats due to lack of space. They can’t go through shallows because they have a keel. They don’t make good canal boats because their masts can’t pass under low bridges. They require a crane or a Travelift for hauling them out for maintenance. They are expensive. They are also quite slow. They can’t carry much freight.

Motor boats are sometimes big enough to make good houseboats. They are either unable to make long ocean passages because of their limited range, or they are expensive to take on ocean passages because of fuel costs. They can go faster than sailing yachts, but then their fuel consumption becomes quite ridiculous. When used as houseboats, their large engines make a poor investment. They also require a crane or a Travelift for maintenance. Some of them can carry a considerable amount of freight, but this makes them slower and increases the fuel consumption.

Houseboats are either houses built on floats or boats that can’t handle rough water. They are reasonable to live on and can be used on rivers and canals, but they can’t venture out on the ocean, never mind make ocean passages. They don’t carry freight.

Houses are great to live in—much roomier than any boat. But they do have two major shortcomings: they don’t move, and they don’t float. This is increasingly a problem: lots of houses are lost to flooding every year, and the toll will only go up as oceans rise and extreme weather events associated with climate change become more frequent. If an area where you have built a house becomes unpleasant or dangerous, you can’t just move the house but have find yourself a new dwelling.

Boats do float, but with most boats nobody particularly wants to live on them on dry land. On land, both yachts and power boats have to be put up on jacks, and then living on them is like living in a treehouse, with a long climb up a ladder just to get home. If a flood causes them to float off the jacks, they are unlikely to settle back onto them. Instead, they fall over and get damaged. Then they don’t float any more.

Houseboats generally do better on dry land than other kinds of boats. The Dutch have built some houses on barges that are designed to float up and down. When the water is low, they bicycle home; when the water is high, they row a dinghy. That’s a good idea in a country that’s mostly under water. But I haven’t heard too many stories about people living on houseboats on dry land.

QUIDNON is specifically designed to do a great number of things adequately.

It makes a reasonable land-based residence that floats when it has to. Its bottom is flat, and it settles upright again once the waters recede. It is a second-floor walk-up, but then its roof makes a wonderful deck, and the cockpit makes a nice gazebo.

It makes a good houseboat of the sort that just stays at the dock: then you can skip the expense of the masts, the sails and the engine, and just live on it. If you want a comfortable, inexpensive DIY dockside dwelling that looks enough like a boat to not bother the neighbors, look no further.

When the time comes to move house, just drop in an outboard engine. It is a good boat for rivers and canals because it only draws a couple of feet. If all you need to do is motor to a different marina twice a year (to shift between summer and winter camp) or to go from a marina to a mooring field and back, there is no need for a dedicated engine. Instead, you can just drop in your dinghy engine into the engine well, then put it back on the dinghy.

If you want to go sailing, add masts and sails. Even with masts and sails added, it still makes a good canal boat, because you can drop the masts by yourself with just a comealong—no crane needed.

If you want to make ocean passages, that is not a problem either. QUIDNON has 130º of stability, making it quite safe, and is reasonably fast for its size, especially downwind. It isn’t fast upwind, particularly in rough seas—but then few people enjoy such a bone-shaking ride in any case. Some people view the ability to go upwind in any conditions as key, forgetting the fact that the entire planet has been explored and settled using boats that couldn’t go upwind any better than about 60º to the wind, tacking through 120-130º. If sailing upwind were important, people would have paid more attention to this problem. The only sailors who valued the ability to sail close to the wind were corsairs—pirates! In fact, most ocean sailing is still done off the wind or downwind, with the prevailing winds. Choose your courses the way the old-time mariners did, and you can even use QUIDNON to circumnavigate. And should you wish to carry a few tons of freight, there is plenty of room for it, and the extra weight won't make much of a difference.

When the time comes to haul out for maintenance, you don’t have to pay a crane operator and a marina. Just find a sandy spot that dries out at low tide, anchor there, and wait for the water to recede. The bottom is surfaced with roofing copper, and you just need to scrape off the seafood that grows on it where you can reach it. The rest of the seafood will get crushed against the sand.

And now, here is the thing that it does ridiculously well: getting around onerous regulations.

If you live in a house, you are subject to an ever-increasing number of regulations. You are limited in what you can build, where you can build it, what materials you can build it out of and what you can use it for. There is a permitting process to follow. You are usually forced to hook it up to utilities and to pay real estate tax on it. You are often required to hire licensed tradesmen to build and maintain a house. All said and done, many people pay close to half of their income just for a place to live. This would indicate that housing is basically a racket.

If you live on a boat, the regulations are few. There is nobody to stop you from building whatever boat you want. There is generally no permitting process, except for mooring permits in certain areas. States will try to charge you for registration, but you can get around this by documenting your boat with the Coast Guard.

There are rarely any issues with storing a boat on land that you own or lease. If you also own or lease the boat, who is to say that you aren’t allowed to live on it? If putting it on land is still problematic, dig a reflecting pool and put QUIDNON in it. Lakes, rivers and harbors are generally considered free to anchor in. If a piece of land is particularly prone to floods, you generally can’t get a building permit to put up a house on it. But there is nothing to stop you from putting a boat on it.

With most boats, when you buy it you pay the designer, the manufacturer and his workers, and the investors’ profits—in addition to all the materials and supplies. With QUIDNON, the design was done by volunteers who designed the boat for themselves, you provide your own assembly labor, and your only costs are the materials and supplies and for somebody to mind the numerically controlled mill to cut out the parts for the kit.

QUIDNON may not be as posh and sporty as a yacht, not as fast as a power boat, and not as roomy as a house. The one thing that it does ridiculously well is set you free. First, there is financial freedom: no rent or mortgage, no real estate taxes, no need to pay tradespeople. Second, there is freedom of movement: sail or motor anywhere you want, stay for as long as you like. Haul it out and use it as a beach house on some nice uninhabited island, then push it back in the water and sail off again.

Ocean yachts are designed for ocean cruising and racing. They make poor houseboats due to lack of space. They can’t go through shallows because they have a keel. They don’t make good canal boats because their masts can’t pass under low bridges. They require a crane or a Travelift for hauling them out for maintenance. They are expensive. They are also quite slow. They can’t carry much freight.

Motor boats are sometimes big enough to make good houseboats. They are either unable to make long ocean passages because of their limited range, or they are expensive to take on ocean passages because of fuel costs. They can go faster than sailing yachts, but then their fuel consumption becomes quite ridiculous. When used as houseboats, their large engines make a poor investment. They also require a crane or a Travelift for maintenance. Some of them can carry a considerable amount of freight, but this makes them slower and increases the fuel consumption.

Houseboats are either houses built on floats or boats that can’t handle rough water. They are reasonable to live on and can be used on rivers and canals, but they can’t venture out on the ocean, never mind make ocean passages. They don’t carry freight.

Houses are great to live in—much roomier than any boat. But they do have two major shortcomings: they don’t move, and they don’t float. This is increasingly a problem: lots of houses are lost to flooding every year, and the toll will only go up as oceans rise and extreme weather events associated with climate change become more frequent. If an area where you have built a house becomes unpleasant or dangerous, you can’t just move the house but have find yourself a new dwelling.

Boats do float, but with most boats nobody particularly wants to live on them on dry land. On land, both yachts and power boats have to be put up on jacks, and then living on them is like living in a treehouse, with a long climb up a ladder just to get home. If a flood causes them to float off the jacks, they are unlikely to settle back onto them. Instead, they fall over and get damaged. Then they don’t float any more.

Houseboats generally do better on dry land than other kinds of boats. The Dutch have built some houses on barges that are designed to float up and down. When the water is low, they bicycle home; when the water is high, they row a dinghy. That’s a good idea in a country that’s mostly under water. But I haven’t heard too many stories about people living on houseboats on dry land.

QUIDNON is specifically designed to do a great number of things adequately.

It makes a reasonable land-based residence that floats when it has to. Its bottom is flat, and it settles upright again once the waters recede. It is a second-floor walk-up, but then its roof makes a wonderful deck, and the cockpit makes a nice gazebo.

It makes a good houseboat of the sort that just stays at the dock: then you can skip the expense of the masts, the sails and the engine, and just live on it. If you want a comfortable, inexpensive DIY dockside dwelling that looks enough like a boat to not bother the neighbors, look no further.

When the time comes to move house, just drop in an outboard engine. It is a good boat for rivers and canals because it only draws a couple of feet. If all you need to do is motor to a different marina twice a year (to shift between summer and winter camp) or to go from a marina to a mooring field and back, there is no need for a dedicated engine. Instead, you can just drop in your dinghy engine into the engine well, then put it back on the dinghy.

If you want to go sailing, add masts and sails. Even with masts and sails added, it still makes a good canal boat, because you can drop the masts by yourself with just a comealong—no crane needed.

If you want to make ocean passages, that is not a problem either. QUIDNON has 130º of stability, making it quite safe, and is reasonably fast for its size, especially downwind. It isn’t fast upwind, particularly in rough seas—but then few people enjoy such a bone-shaking ride in any case. Some people view the ability to go upwind in any conditions as key, forgetting the fact that the entire planet has been explored and settled using boats that couldn’t go upwind any better than about 60º to the wind, tacking through 120-130º. If sailing upwind were important, people would have paid more attention to this problem. The only sailors who valued the ability to sail close to the wind were corsairs—pirates! In fact, most ocean sailing is still done off the wind or downwind, with the prevailing winds. Choose your courses the way the old-time mariners did, and you can even use QUIDNON to circumnavigate. And should you wish to carry a few tons of freight, there is plenty of room for it, and the extra weight won't make much of a difference.

When the time comes to haul out for maintenance, you don’t have to pay a crane operator and a marina. Just find a sandy spot that dries out at low tide, anchor there, and wait for the water to recede. The bottom is surfaced with roofing copper, and you just need to scrape off the seafood that grows on it where you can reach it. The rest of the seafood will get crushed against the sand.

And now, here is the thing that it does ridiculously well: getting around onerous regulations.

If you live in a house, you are subject to an ever-increasing number of regulations. You are limited in what you can build, where you can build it, what materials you can build it out of and what you can use it for. There is a permitting process to follow. You are usually forced to hook it up to utilities and to pay real estate tax on it. You are often required to hire licensed tradesmen to build and maintain a house. All said and done, many people pay close to half of their income just for a place to live. This would indicate that housing is basically a racket.

If you live on a boat, the regulations are few. There is nobody to stop you from building whatever boat you want. There is generally no permitting process, except for mooring permits in certain areas. States will try to charge you for registration, but you can get around this by documenting your boat with the Coast Guard.

There are rarely any issues with storing a boat on land that you own or lease. If you also own or lease the boat, who is to say that you aren’t allowed to live on it? If putting it on land is still problematic, dig a reflecting pool and put QUIDNON in it. Lakes, rivers and harbors are generally considered free to anchor in. If a piece of land is particularly prone to floods, you generally can’t get a building permit to put up a house on it. But there is nothing to stop you from putting a boat on it.

With most boats, when you buy it you pay the designer, the manufacturer and his workers, and the investors’ profits—in addition to all the materials and supplies. With QUIDNON, the design was done by volunteers who designed the boat for themselves, you provide your own assembly labor, and your only costs are the materials and supplies and for somebody to mind the numerically controlled mill to cut out the parts for the kit.

QUIDNON may not be as posh and sporty as a yacht, not as fast as a power boat, and not as roomy as a house. The one thing that it does ridiculously well is set you free. First, there is financial freedom: no rent or mortgage, no real estate taxes, no need to pay tradespeople. Second, there is freedom of movement: sail or motor anywhere you want, stay for as long as you like. Haul it out and use it as a beach house on some nice uninhabited island, then push it back in the water and sail off again.

Friday, April 21, 2017

Announcing: QUIDNON Crowdfuding Campaign

For the next month or so we will be trying to raise money to build the first QUIDNON. If you want to see this project realized, please consider making a contribution.

We have t-shirts, posters and books for those who donate.

And if you donate $500 or more (USD) we will do our best to deduct the amount of your donation from the price of your eventual order of the QUIDNON kit (if and when it becomes available).

Friday, April 7, 2017

A Guided Tour

There are lots of exciting developments for this project. First, we are zeroing in on the design, putting the finishing touches on various pieces. Second, we are about to announce the crowdfunding campaign to the world, so stay tuned.

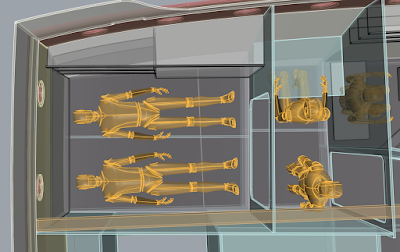

In this post I will provide a look at all the more important elements of the design by presenting and narrating detailed views of the 3D model.

We start our tour underwater, as a scuba diver would, approaching a floating QUIDNON from below.

The hull is shown as translucent, to allow you to see the very substantial internal structure. The two keelboards and the two rudder blades hang down at a 10º angle, which is optimal for when the hull is heeled, since a hull this wide (16 feet) isn't going to heel more than about 10º.

The circles on the keelboards (and the rudder blades further aft) are where plates of led ballast will be embedded in the plywood sandwich. The extra weight is enough to oppose the buoyancy of the blades, allowing them to drift down when sailing slowly, but keeping them light enough so that they can bounce off the bottom in the shallows without suffering damage. When sailing fast, downhaul lines keep the keelboards and the rudder blades down against the resistance of the water rushing past. The downhauls are secured using autorelease cam cleats that pop open if a keelboard or a rudder blade encounters something solid. The skipper would then wake up and do an emergency 180º turn, or look at the depth sounder, shrug, and re-tighten and re-secure the downhaul that just popped.

Along the chines between the sides and the bottom are chine runners. They are designed to provide lateral resistance when sailing through shallows, with the keelboards raised, or bouncing along the bottom ineffectually. This feature allows QUIDNON to tack through a shallow spot that only has around 2 feet of water and also allows it to sail off the wind with the keelboards raised, decreasing drag.

The propeller from the outboard engine, in its inboard outboard well, is visible further aft. The engine moves up and down on a track, and can be raised while sailing, to further reduce drag.

Floating gently toward the transom, we notice an interesting recess in the bottom just forward of the engine well. That is where the solid ballast is hung. It is externally mounted, so that it can be dropped before hauling out on a beach, then winched into place once afloat again. It consists of a cement block with steel scrap embedded in it. It's got an eye for attaching a line in its center and 4 pieces of threaded rod—one in each corner. To mount it in place, somebody has to dive down and tie a line to the eye, then stick that eye through a hole in the center of the chain locker, which is right above where the ballast block goes and right below the cockpit. The block is then pulled into position using a comealong. Once in position, the 4 pieces of threaded rod poke through openings in the bottom of the chain locker and secured using nuts.

Finally, we reach the transom, which is going to have a swim step and a boarding ladder, but they aren't shown because we aren't done designing them yet. Note that the bottom is slightly flared as it reaches the transom. This is to provide clearance for the rudder assembly, which is tilted 10º. Also note the recess in the center of the transom, which is to keep the stream of water from the propeller from hitting the transom. For those interested in QUIDNON trivia, the horizontal panel right above that recess is officially called "the taint."

The rudder posts (pipes, actually) are bent forward slightly, so that the pivot point of the rudder blades is forward of their axis. This is done so that it is possible to adjust the angle of the rudder blades so that the steering is as close to completely neutral as you like, to provide fingertip steering, and to keep the autopilot from wasting energy. Most rudders pivot around their leading edge, or close to it, and take a lot of power to deflect. Some people find that sort of steering "sporty." But what works best is when rudder blades are adjusted so that they trail in the water if allowed to move freely but can be deflected with hardly any effort at all.

Climbing aboard using the imaginary swim step and boarding ladder, we see the cockpit populated by two creepy mannequins (they are very useful for figuring out ergonomics, but we are looking for better-looking ones). The seated mannequin is holding onto an imaginary tiller. Yes, QUIDNON uses tiller steering instead of wheel steering, for the following reasons:

1. Whether wheel or tiller, hand-steering is rarely done, because most of the steering is done by autopilot. I generally turn on autopilot seconds after casting off and turn it off again seconds before anchoring or docking. But a wheel clutters up the cockpit the entire time, while the tiller can be folded away when it isn't being used.

2. When you do have to hand-steer it is usually when docking or casting off, and what you want is a tiller anyway, so that you can freely swing it from side to side, instead of having to spin the wheel.

3. Most of the reason to use a wheel is that it allows for a lot of leverage. But who needs leverage when you have neutral steering? The only time you won't have neutral steering on QUIDNON is when you are in the shallows and the rudder blades are kicking up, but then you should slow the heck down immediately. And if you are moving slowly you don't need amplification anyway.

4. If you find that you need to hand-steer for a long time—if the autopilot dies, or if you need to hand-steer because you are ghosting to windward in a fickle breeze and the "sail to wind" function isn't working—then what you want is a tiler, not a wheel. With a wheel, there is just one steering position: standing behind the wheel. With a tiller, you can sit, stand, recline, use your feet, use your hips, tuck the tiller extension under your armpit or rig something up using bungee cords and a line tied to one of the sheets.

Here are the details of QUIDNON's steering linkage. Rudder arms and the tie-rod that connects them are shown in purple. The tie-rod is slightly shorter than the distance between the rudder posts. This is called Ackermann geometry, and allows the boat to efficiently pivot around the keelboards without generating drag, because the rudder blade closer to the center of the circle is deflected farther than the other. Along the centerline is the tiller, connected to one of the rudder arms using a diagonal linkage which allows a certain amount of amplification, to limit the swing range of the tiller to the confines of the cockpit. The tiller is a telescoping tiller that consists of a housing, the tiller itself, and the tiller extension.

Below the steering linkage is the equipment chase. QUIDNON's aft section consists of 2 aft cabins, and between them is a wedge-shaped space taken up by everything that doesn't belong in the cabin. Working from the transom forward, the rearmost section houses the gas tank and two 20-lb. propane cylinders. Forward of that is the engine well. Forward of the engine well, we have the solid ballast block at the bottom, the chain locker above it, and the cockpit well above that.

Here is another view of the cockpit. Note that there are lots of places to sit: down below, with your feet in the cockpit well; up above, on the raised lazarettes, with your feet on the seats, and inside the dodger if the weather is nasty. And you can hand-steer using the tiller extension no matter where you sit.

But you will probably be spending most of the time down below in the cabin, which is accessed using the companionway hatch and the companionway ladder.

This ladder is built right into the structure of the boat and is much more comfortable to use than most companionway ladders found on sailboats of this size. It is also much more than the ladder. At the bottom it has a footwear locker. Next, behind the first step, is a row of plumbing valves. Above it is a row of switches that control various pumps and alarms. Above it is the AC 110V/220Vcontrol panel, for shore power. And above that is the DC 12V control panel. This is a very convenient place to put all this stuff, from every angle.